What Is a Tax Lien?

A tax lien is a legal claim by a government against your property when you fail to pay taxes. It is not the same as a levy, which actually seizes assets, but it creates a public record showing the government’s right to your home, business assets, or other property.

Tax liens damage credit, restrict your ability to sell or refinance property, and signal serious collection efforts.

Both the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and state revenue agencies can file tax liens. While the concept is the same, the process, thresholds, and options differ depending on whether the lien is federal or state.

Who Files the Lien — IRS vs. State Revenue Agencies

- IRS Federal Tax Lien: Filed by the Internal Revenue Service after a tax bill goes unpaid. It applies nationwide, affecting all property and future assets.

- State Tax Lien: Filed by a state Department of Revenue, Franchise Tax Board, or Comptroller’s office. It applies within that state, but many states coordinate with credit bureaus and local courts, so the lien is visible even outside the state.

Crucially, a federal tax lien and a state tax lien are separate. You could face both simultaneously if you owe taxes to multiple jurisdictions.

Example: Someone owing $12,000 to the IRS and $2,000 to California may face two liens at once — one federal and one state. Each lien follows its own process, and both would have to be cleared to refinance a home.

Thresholds and Triggers for Filing

The IRS generally files a Notice of Federal Tax Lien once your unpaid balance exceeds $10,000, though it has discretion to act earlier or later. The notice is usually filed after the IRS sends multiple bills and you fail to pay.

States vary significantly:

- California: The Franchise Tax Board can file a lien for balances as low as a few hundred dollars.

- New York: Liens may be filed as soon as a liability is assessed and demand for payment is ignored, sometimes under $2,000.

- Texas: The Comptroller tends to wait until larger balances build, but once filed, enforcement is strict.

This inconsistency makes state tax liens harder to predict. Someone might owe $5,000 to the IRS without a lien, but a $1,000 state balance could trigger immediate action.

Enforcement and Collections

Federal Enforcement Tools

Once a Notice of Federal Tax Lien is filed:

- The lien attaches to all property and rights to property, including future assets.

- It severely impacts your credit rating and may prevent you from obtaining loans.

- If unpaid, the IRS may escalate to a levy, seizing bank accounts, wages, or property.

State Enforcement Tools

States may be more aggressive in some respects:

- Property seizure: Some states move quickly to seize real estate or vehicles.

- Wage garnishment: States often have streamlined garnishment authority.

- Local leverage: Because states operate closer to taxpayers, they may suspend driver’s or professional licenses.

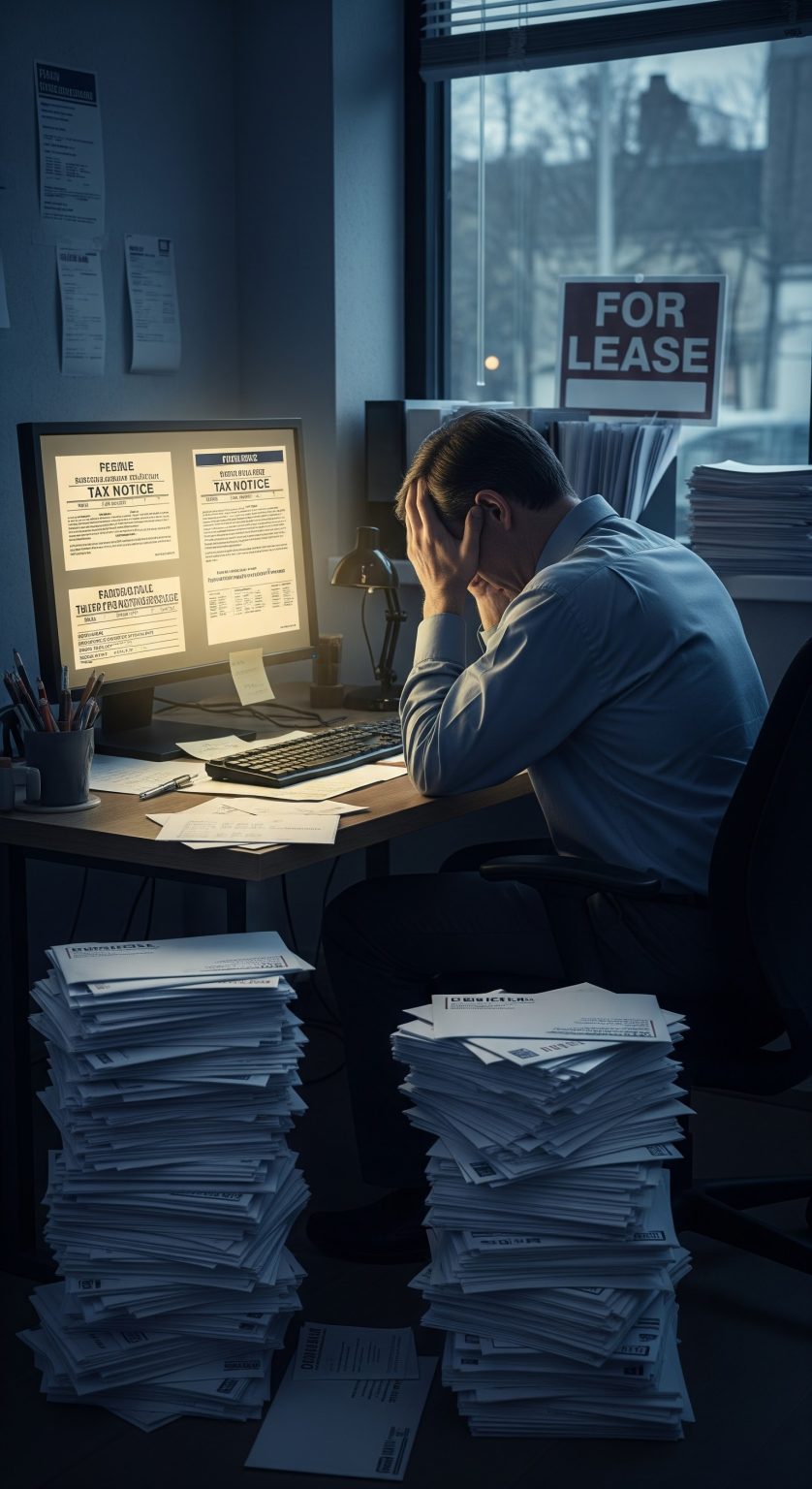

- Credit and lending impact: Both IRS and state liens appear on public records, but state liens can be especially damaging when lenders see “local court judgment” language. For small businesses, a state lien may prevent renewing supplier contracts or leasing office space.

Example: A small business owner in New York with a $1,500 state lien may find local banks unwilling to extend credit, even though the IRS has not yet acted.

Resolution Options — IRS vs. State

IRS Options

The IRS has established programs to resolve liens, including:

- Offer in Compromise (OIC): Settle for less if you qualify.

- Installment Agreement: Pay over time; in some cases, the lien may be withdrawn.

- Lien Withdrawal: Possible if you enter a Direct Debit Installment Agreement and meet requirements.

- Lien Release: Once the balance is fully paid, the lien is released within 30 days.

- Lien Discharge or Subordination: Allows sale or refinancing of property under certain conditions.

State Options

Each state sets its own rules. Common programs include:

- Installment Agreements: Monthly payments are standard, but terms vary widely. Some states require higher minimum payments than the IRS.

- Hardship or Temporary Deferrals: States like California may allow temporary hardship status; others may not.

- Appeals Boards: Taxpayers can sometimes challenge the lien, though processes are often less formal than IRS appeals.

- Settlement Programs: A few states, such as California and New York, have limited Offer in Compromise programs. In contrast, Texas generally expects payment in full and offers fewer formal settlement avenues.

Because of these differences, resolving a state tax lien can require state-specific expertise. A strategy that works with the IRS may not apply at the state level.

How State and Federal Liens Interact

State and federal liens operate independently. Having one does not block the other from being filed. This can lead to situations where both liens attach to the same property.

When multiple liens exist, priority rules apply:

- The lien filed first usually has priority in claims against property.

- A state lien filed before a federal lien may take precedence, but the IRS can still levy assets once the lien is in place.

Dual liens make property transactions more complex. A homeowner may need to satisfy both liens before refinancing a mortgage or selling real estate.

Preventing a Tax Lien at Any Level

Whether you owe the IRS or your state:

- Respond early to notices. The earlier you act, the more options are on the table.

- Set up a payment plan. Both IRS and states allow installment agreements, though terms differ.

- Provide financial documentation. Agencies are more flexible if you can show income, expenses, and hardship.

- Consider professional guidance. A tax professional can navigate both IRS and state rules simultaneously.

- Monitor both federal and state obligations. Some taxpayers resolve their IRS balance only to be surprised later by a state lien. Staying current on both fronts is essential.

Preventive action is especially important with state taxes since thresholds are lower and enforcement is often faster.

Key Takeaways

- IRS liens are nationwide, with structured relief programs.

- State liens vary widely, sometimes filing for much smaller debts.

- Both harm credit and restrict property rights.

- Having both can create double financial pressure.

The best defense is early communication and proactive resolution.